Agnes Edith Metcalfe

In terms of women and Gray’s Inn in 1903 the focus was very emphatically on Bertha Cave and her appeal, for obvious reasons. However, at the same Pension meeting on 24 April 1903 that ordered her application to be rejected, a second application by a woman was also considered, which was summarily dealt with:

In terms of women and Gray’s Inn in 1903 the focus was very emphatically on Bertha Cave and her appeal, for obvious reasons. However, at the same Pension meeting on 24 April 1903 that ordered her application to be rejected, a second application by a woman was also considered, which was summarily dealt with:

“Read an application by Miss Agnes Edith Metcalfe, a Bachelor of Science of London University, for admission as a student for the purpose of being called to the Bar. Resolved that no order be made upon the application.”

In other words, no.

Miss Metcalfe did not reapply, understandably in the light of the outcome of Bertha Cave’s appeal. There is no further documentation surviving in Gray’s Inn relating to her or her application, nor is there any equivalent of the 1904 press coverage of the bicycle hearings which gave the additional information on Bertha Cave’s background that made it possible to identify her. Nevertheless, there was apparently only one Agnes Edith Metcalfe in the country of the right age, who in addition was associated over many years with the women’s suffrage movement, so this seems a highly likely identification.

Agnes Edith Metcalfe was born in 1870 in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, into a well-established professional family, the youngest of the three daughters of Frank Metcalfe and his wife Judith (nee Hopkinson). Agnes’ father, grandfather and uncle were solicitors in Wisbech; her grandfather and uncle were successively Clerks of the Peace of the Isle of Ely, and successively seated at Inglethorpe Hall, Emneth, while her father, until his early death at the age of 43 in 1885, was clerk of the court at Wisbech. Her maternal grandfather had been a clergyman in nearby Huntingdonshire.

Agnes was educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College up to degree level: she obtained there in 1892 an external University of London Bachelor of Science degree, as mentioned in her application to Gray’s Inn. She then took up a career as a schoolteacher and in 1897 was appointed Head Mistress of Stroud Green School in North London, living at the time of the 1901 census in nearby Hornsey. In 1905 she was appointed the first Head Mistress of the new Sydenham County Council School. In 1907 she became a School Board Inspector of Secondary Schools.

There is no trace of her in the 1911 Census, which it seems likely that she evaded, as did many other supporters of women’s suffrage, on the basis that if women were not to be recognised as persons by the law then the government could not really expect them to allow themselves to be counted for any other purpose.[Jill Liddington: Vanishing for the Vote, MUP 2014]. In 1913 [The Vote, 19 Dec 1913] and 1917 [A E Metcalfe: Women’s Effort, 1917, title page] she was described as “late HMI (Secondary Schools)”, so seems to have given up work rather early. She was at some point Treasurer of the Women’s Tax Resistance League (founded in 1909). The idea behind this was basically “no taxation without representation”: women and their supporters refused to pay various taxes and when their goods were distrained for sale, the resultant publicity highlighted the injustice of the situation. Imprisonment for short periods was also possible. Agnes Metcalfe was herself taken to court at Greenwich, as described in the following article from “The Vote”, 19 December 1913:

“Miss A[gnes Edith] Metcalfe, B.Sc., ex-H.M.I., was summoned at Greenwich Police-court on Tuesday, December 9, for non-payment of [a] dog license. In a short speech she said that she refused on conscientious grounds to pay taxes while women had no vote. The magistrate congratulated Miss Metcalfe on the clearness and eloquence with which she made out her case. He regretted that the law must take its course, and imposed a fine of 7s. with 2s. costs, recoverable by distraint. The alternative was one day’s imprisonment. We would like to contrast this with Miss I[sabelle] Stewart’s case which was identical, but her sentence was £2 fine or fourteen days’ imprisonment.”

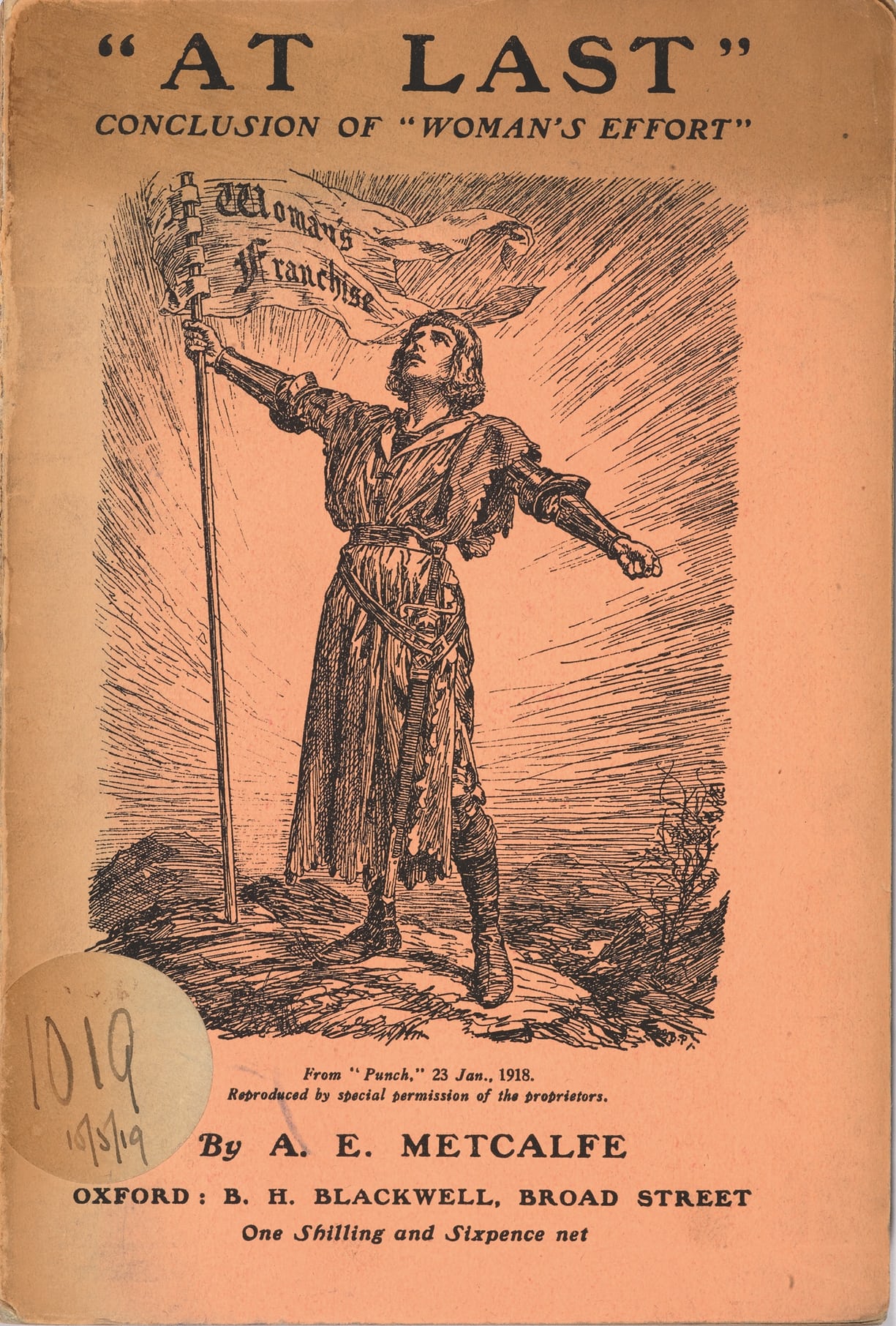

She later wrote on women’s suffrage issues. Her first book, published in 1917, was “Women’s Effort: A Chronicle of British Women’s Fifty Years’ Struggle for Citizenship (1865-1914)”, which had an introduction by the distinguished suppporter of women’s rights, Laurence Housman. This was followed by “Woman, A Citizen” in 1918 and “‘At Last’: Conclusion of Women’s Effort” in 1919 (illustrated below).

She died in 1923. Her estate was used to establish the Metcalfe Studentships for Women at LSE, awarded to female postgraduate students undertaking research on some social, economic or industrial problem.

Agnes Metcalfe was far more typical than Bertha Cave, in her background and education, of the women who were admitted to the Inn after 1919. It is not clear what exactly prompted her application in 1903; possibly she was working in conjunction with others to put pressure on Gray’s Inn to speed up their response to Bertha Cave’s initial application in March.

The front cover of Agnes Metcalfe’s final work, celebrating the legislative reforms of 1919

Apart from details of the Metcalfe family background, which are from directories and censuses, this article is mostly based on the obituary of Agnes Metcalfe published in “The Vote”, 26 Oct 1923, provided by the kindness of Sue Donnelly, Archivist of the LSE, and Gillian Murphy, Curator of the Women’s Library at the LSE.

Andrew Mussell, Former Archivist at Gray’s Inn.

August 2017